Harmonising Selenium with Playwright and Cypress: A Journey Through Network Event Handling

on Blog

Introduction

Harnessing Network Events in Testing

Playwright and Cypress are well-known for their ‘autowait’ feature. This neat trick aligns elements seamlessly and avoids many ‘test flake’ issues, like Selenium’s StaleElementException and NoSuchElementException. However, I’m skeptical about this so-called ‘magic’ in testing. A reliable test should avoid unexpected variables that are meant to simplify the process. I don’t like accepting hidden 3rd party logic influencing my tests without scrutiny; I believe in thoroughly dissecting and analyzing everything to ensure test reliability. A deep understanding is also very valuable for troubleshooting and grasping what tests are actually doing with whatever’s under test.

This post will reveal a particular feature of these tools that, in my experience, is central to what makes them useful. I’ll cover how this feature can also be backported to historic Selenium frameworks to enhance the trustworthiness of your tests. This feature is granular control over Network Events.

When you have control over network events, it becomes much easier to ensure that your test actions align with what’s happening in a structured manner. I’ve encountered situations where a test couldn’t perform certain actions due to network issues, and there were no clear indicators on the screen. The application might be sending or receiving data in a way that prevents the user from taking action, among other issues. Additionally, unpredictable changes in network speed can disrupt the test. However, by using code to check if requests are in a “settled” state before proceeding, you can avoid this common problem that leads to unpredictable test behavior.

Stability vs. Exact Duplication

I wouldn’t go so far as to say I universally endorse controlling network events despite talking about it here. As always, you are the best judge of the appropriate level of testing for the shippable quality of whatever’s under test. What forms an appropriate abstraction of “if these tests pass that then this change is shippable” is very dependent on context. While I have found using techniques like these useful in taming an unruly application, this was as a result of discussion and agreement within the whole team. Ultimately, we agreed increased test stability an acceptale tradeoff for not having a perfectly exact duplicate of the environment a user would use. Extensively manipulating network requests may also tie your tests to implementation details of the backend that may not be intended or appropriate.

This blog post will also not explore the suitability of tests written using Selenium, Playwright, or Cypress. Targetting tests at the appropriate layer is a whole subject in and of itself. I will therefore generally assume you are writing tests with reference to The Practical Test Pyramid model and The Way of Testivus.

Test Flake

Test flake refers to the problem when testing yields inconsistent results on each run. Many people mistakenly believe that Selenium, a testing tool, is plagued by this issue, but it’s not inherently unreliable. Selenium follows the W3C WebDriver rules and uses web commands to control the browser. This method can sometimes cause small delays and chances for errors between starting an action and finishing it. Also, Selenium has ways to wait for things to happen, but it doesn’t automatically sync like newer tools do. This means testers have to do more work themselves. Plus, when you mix different ways of testing and complicated web designs, it seems like Selenium is more unreliable than it actually is. But really, Selenium is doing its job as it’s supposed to, within its own limits.

Playwright and Cypress’ Approach to Harnessing Network Events

Playwright: Network Events and CDP

Playwright integrates with the browser’s developer and debugging protocols. It uses this to listen and respond to browser lifecycle events, checks for their completion, and provides an array of tools for controlling and automating other browser actions.

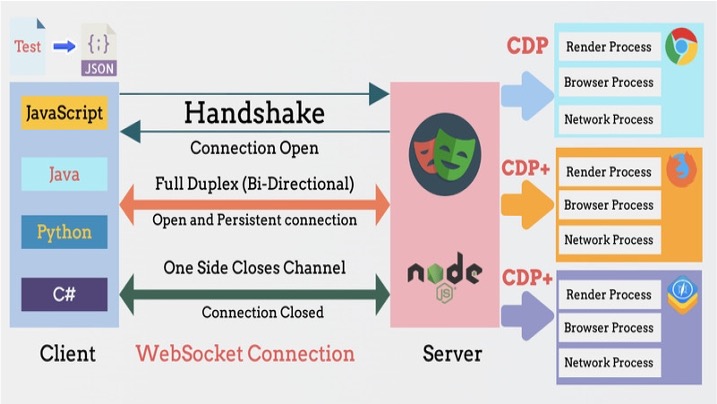

Image credit: ProgramsBuzz

Putting aside the left hand side of the diagram for now, notice how the Playwright NodeJS server is shown to use CDP. CDP stands for Chrome DevTools Protocol. What’s that?

From the CDP documentation:

The Chrome DevTools Protocol allows for tools to instrument, inspect, debug and profile Chromium, Chrome and other Blink-based browsers.

Instrumentation is divided into a number of domains (DOM, Debugger, Network etc.). Each domain defines a number of commands it supports and events it generates. Both commands and events are serialized JSON objects of a fixed structure.

Internally, Playwright uses specific domains and commands to control the browser in detail. While the process of setting up event listeners and using these commands is complex and not explained here, it allows Playwright to offer a variety of browser functions through its public API that users interact with. The domain we are most interested in for this blog is the Network domain.

Note: the CDP is why, at launch, Playwright only supported Chromium based browsers. As time has gone on, non-Chromium browsers are supported by analagous systems for controlling the broser in a similar way. But, at the time of writing, there are still some features missing from these implementations (such as modifying requests on the fly, performance data, heap snapshots, etc).

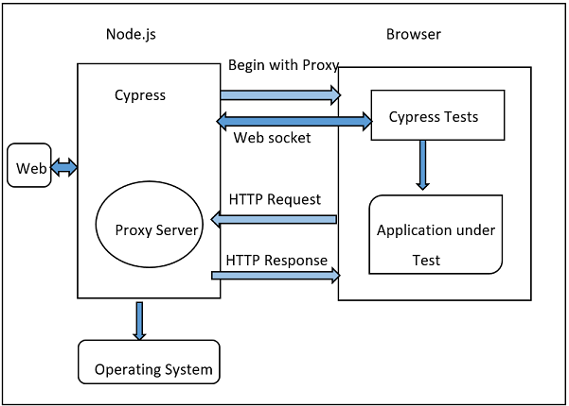

Cypress: Network Events and Network Proxying

By contrast, Cypress achieves this level of control by proxying network events through itself. Cypress also owes some of its speed to being within the same run-loop as the browser it’s using, allowing for fine grain control and debug options in that way.

Image credit: Tutorialspoint

Because Cypress stands in between the browser and the Internet it therefore affords Cypress complete control over associated events, notifying itself when events are dispatched, received back, allowing for manipulation of requests, connection speed profiling, etc.

Note: early versions of Selenium (RC) worked in the same way as Cypress (through JS) before that was ditched in favour of external drivers communicating with the JSON wire protocol. Cypress effectively also runs in its own iframe, which is partly why it has longstanding problem with testing applications with them (though I understand steps have been taken to help deal with this limitation).

Selenium

Selenium, by contrast, has only fairly recently supported access to the CDP in Selenium 4. In my opinion, Selenium’s tone is quite dismissive of the CDP. I suppose this is generally because Selenium’s approach has (and continues to be) that waiting for elements to be visible to the user to determine when to take actions and when to not is the best approach. Unfortunately, however, I believe this approach is too simple. It works well for older web applications that are more predictable. But in today’s world, where technologies like React make web pages more dynamic and technologies like shadow DOM are used, Selenium’s way of testing websites may not be as effective.

Code Examples

Mimicking Playwright’s Approach With Selenium

Note: all of my examples will use Python for readability, but it’s obviously possible to do all this and more with other Selenium bindings as well.

As already discussed, the CDP allows for very granular control over network activity. Here, we are using the Network domain’s requestWillBeSent and responseReceived commands to monitor when requests are sent and when requests are received. Selenium has various other ways of using CDP, logging those events is just one. You can also do interesting things like modify outgoing requests and incoming responses, simulate network conditions, etc. Maybe I’ll explore those in the future, who knows!

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

from selenium.webdriver.common.desired_capabilities import DesiredCapabilities

import time

import json

# your path to chromedriver

chrome_driver_path = './chromedriver'

# enable Chrome performance logging for granular network event information (using CDP)

capabilities = DesiredCapabilities.CHROME

capabilities['goog:loggingPrefs'] = {'performance': 'ALL'}

# setup chrome

service = Service(executable_path=chrome_driver_path)

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=service, desired_capabilities=capabilities)

# navigate to desired website

driver.get("https://josephward.tech/")

# initialise an empty set for keeping track of open/closed network events

sent_requests = set()

received_responses = set()

# initialise a timer

start_time = time.time()

timeout = 30

while True:

# check in log for events

logs = driver.get_log('performance')

for log in logs:

event = json.loads(log['message'])['message']

method = event['method']

if 'params' in event and 'requestId' in event['params']:

request_id = event['params']['requestId']

# if method of event is Network.requestWillBeSent add its ID to sent requests

if method == 'Network.requestWillBeSent':

sent_requests.add(request_id)

# if method of event is Network.responseReceived add its ID to sent requests

elif method == 'Network.responseReceived':

received_responses.add(request_id)

if request_id in sent_requests:

# log and print matched events and outstanding from total

print(f"Matched Request and Response: {request_id}")

print(f"Remaining unmatched requests: {len(sent_requests) - len(received_responses)}")

# check if all requests have received responses by comparing set. if matched, end program

if sent_requests == received_responses:

print("All requests have been matched with responses.")

break

if time.time() - start_time > timeout:

print("Timed out waiting for responses.")

break

time.sleep(0.5) # rerun check every interval

# finally, close the browser

driver.quit()

Mimicking Cypress’ Approach With Selenium

Cypress creates its own proxy for network events. By installing BrowserMob proxy we can mimic this. BrowserMob proxy also has an API for granular network interception that allows us to rewrite requests, responses, and other things. Just like CDP.

From BrowserMob Proxy’s documentation:

BrowserMob Proxy allows you to manipulate HTTP requests and responses, capture HTTP content, and export performance data as a HAR file. BMP works well as a standalone proxy server, but it is especially useful when embedded in Selenium tests.

from browsermobproxy import Server

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

from selenium import webdriver

import time

import hashlib

# your path to browsermob proxy and chromedriver

bmp_path = './browsermob-proxy-2.1.4/bin/browsermob-proxy'

chrome_driver_path = './chromedriver'

# start the proxy

server = Server(bmp_path)

server.start()

proxy = server.create_proxy()

# setup chrome to use proxy

options = webdriver.ChromeOptions()

options.add_argument('--proxy-server={0}'.format(proxy.proxy))

options.add_argument('--ignore-certificate-errors') # needed as browsermob proxy has no cert in this example

service = Service(executable_path=chrome_driver_path)

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=service, options=options)

# create a HTTP Archive Format (HAR)

proxy.new_har("test")

# navigate to desired website

driver.get("https://josephward.tech/")

# initialise an empty set for keeping track of open/closed network events

sent_requests = set()

received_responses = set()

# initialise a timer

start_time = time.time()

timeout = 30

while True:

# get HAR log

har_log = proxy.har['log']

# process entries in HAR log

for entry in har_log['entries']:

request = entry['request']

response = entry['response']

# add unique identifier to each entry

request_details = f"{request['url']}_{request['method']}_{entry['startedDateTime']}"

request_id = hashlib.md5(request_details.encode()).hexdigest()

# add request to set (checking if it's there) then log it

if request_id not in sent_requests:

sent_requests.add(request_id)

print(f"Request Sent: {request_details}")

# add response to set (checking if it's there) then log it

if response['status'] and request_id not in received_responses:

received_responses.add(request_id)

print(f"Response Received: {request['url']} with status {response['status']}")

# print progress

print(f"Total Requests Sent: {len(sent_requests)}")

print(f"Total Responses Received: {len(received_responses)}")

print(f"Remaining unmatched requests: {len(sent_requests) - len(received_responses)}")

# check if all requests have received responses

if sent_requests == received_responses:

print("All requests have been matched with responses.")

break

if time.time() - start_time > timeout:

print("Timed out waiting for responses.")

break

time.sleep(0.5) # rerun check every interval

# finally, close the browser and stop the proxy

driver.quit()

server.stop()

A Third Way: Monkey Patching

By injecting JavaScript we can monkey patch the browser’s internal methods for sending requests and receiving responses. This allows us to extend how the browser works on the fly with whatever extra code we want. While this is quite powerful, notice that the JavaScript has to be injected after the page has loaded. Full page navigation will also reset the injected JavaScript, meaning this is typically only useful on single page applications, on features within a web application that won’t cause page navigation, etc. So it has both flexibility but some fairly obvious limitations.

I have probably used some form of browser monkey patching most often of all out of everything we have discussed so far. It has multi-browser support, doesn’t require you introduce another dependencym and is easily injected and cleared ad hoc.

Note: Although we are monkey patching XMLHttpRequest this works equally well with fetch if that’s what’s under test is using. The code below introduces a small memory leak (due the objects we create to track hanging around in memory), but this shouldn’t be problematic for a single test and is easy to do if needed.

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

from selenium import webdriver

import time

import hashlib

# your path to browsermob chromedriver

chrome_driver_path = './chromedriver'

# setup chrome

service = Service(executable_path=chrome_driver_path)

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=service)

# navigate to desired website

driver.get("https://josephward.tech/")

# define and execute the XMLHttpRequest monkey patch

js_script = """

window.openedRequests = window.openedRequests || {}; // initialise empty object for tracking (or use existing)

window.closedRequests = window.closedRequests || {}; // initialise empty object for tracking (or use existing)

(function() {

// first we should check if this monkey patch has already been applied

if (window.__myCustomXMLHttpRequestHandlerInjected) {

return;

}

// if monkey patch not already applied, let's say it has

window.__myCustomXMLHttpRequestHandlerInjected = true;

var oldSend = XMLHttpRequest.prototype.send; // we retain a reference to the original

var oldOpen = XMLHttpRequest.prototype.open; // we retain a reference to the original

// Intercept XMLHttpRequest open method to assign a unique ID and track the request

XMLHttpRequest.prototype.open = function(method, url) {

this.requestId = Math.random().toString(36).substr(2, 9); // Generate a unique ID

window.openedRequests[this.requestId] = {

url: url,

method: method,

content: null

};

return oldOpen.apply(this, arguments); // using original reference

};

// Intercept XMLHttpRequest send method to track when the request is complete

XMLHttpRequest.prototype.send = function() {

var requestId = this.requestId;

var originalOnReadyStateChange = this.onreadystatechange; // retain original handler (avoids breakages)

this.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (originalOnReadyStateChange) {

originalOnReadyStateChange.apply(this, arguments); // first call original handler

}

if (this.readyState === 4) { // this readyState means the request has completed

window.closedRequests[requestId] = {

url: window.openedRequests[requestId].url,

method: window.openedRequests[requestId].method,

content: this.responseText

};

}

};

return oldSend.apply(this, arguments);

};

})();

"""

# execute the JavaScript code on the page

driver.execute_script(js_script)

# wait for some time for the page to load (note: you shouldn't do this in a real test, i am doing it here for demo purposes!)

time.sleep(5)

# click a link

element = driver.find_element("xpath", "//*[contains(text(),'Tech Talks')]")

driver.execute_script("arguments[0].click();", element) # my website is silly so i need to do a jsclick. sorry

timeout = 30

consecutiveZeroTarget = 3 # number of consecutive zero checks before exit

consecutiveZeroCount = 0 # current count of consecutive zeros

start_time = time.time()

while True:

# Check the contents of both opened and closed requests arrays using injected javascript

opened_requests = driver.execute_script("return window.openedRequests;");

closed_requests = driver.execute_script("return window.closedRequests;");

print(f"Opened requests: {opened_requests.keys()}")

print(f"Closed requests: {closed_requests.keys()}")

if opened_requests.keys() == closed_requests.keys(): # match object

consecutiveZeroCount += 1

print(f"Consecutive zero count: {consecutiveZeroCount}")

if consecutiveZeroCount >= consecutiveZeroTarget:

break

if time.time() - start_time > timeout:

print("Timed out waiting for all requests to complete.")

break

time.sleep(0.5) # rerun check every interval

# finally, close the browser

driver.quit()

Closing Thoughts

Cypress and Playwright are very powerful. You can leverage some of what makes them powerful and port them over to Selenium 3 or 4. How and if you use these tools is up to you, but I have found it very useful to make the tests of my projects more robust by having more granular control of network events (by whatever method is appropriate). Ultimately, whether these methods are useful to you depends on the tradeoffs you are willing or able to make in order to vouchsafe the shippable quality of whatever’s under test in a responsible and accurate way.